These Documentaries Will Move You To Tears

Introduction by Anh-Minh Le

Cover photo by Kelsey Wisdom

A few years ago, Anna Richardson White and Conall Jones were introduced by a mutual friend who figured that the two local filmmakers should know one another. After all, Carmel Valley, which they both now call home, isn’t exactly a film industry hub. Seated together in White’s living room, she confirms to Jones: “You’re my one friend in Carmel Valley who makes films.”

They first met up at Lighthouse Cinema for a local documentary screening. Soon after, Jones—a Carmel Valley native and Academy Award-nominated producer—watched “Appalheads,” White’s first-ever film, and a deeply personal project for the media and communications executive.

“Appalheads” draws its name from Appalshop, the nonprofit arts organization founded by White’s father in Whitesburg, Kentucky, the small rural town where she grew up. Appalshop dates to 1969, when it began as a community film workshop. In the documentary, White returns home to explore her roots, and along the way, delves into her father’s dementia and the historic 2022 floods that wreaked havoc on Whitesburg–including damaging Appalshop’s archives. The film has been playing on the festival circuit this year, winning Best Documentary at California’s Sundial Film Festival and an Appalachian Voices Award at the Appalachian Film Festival.

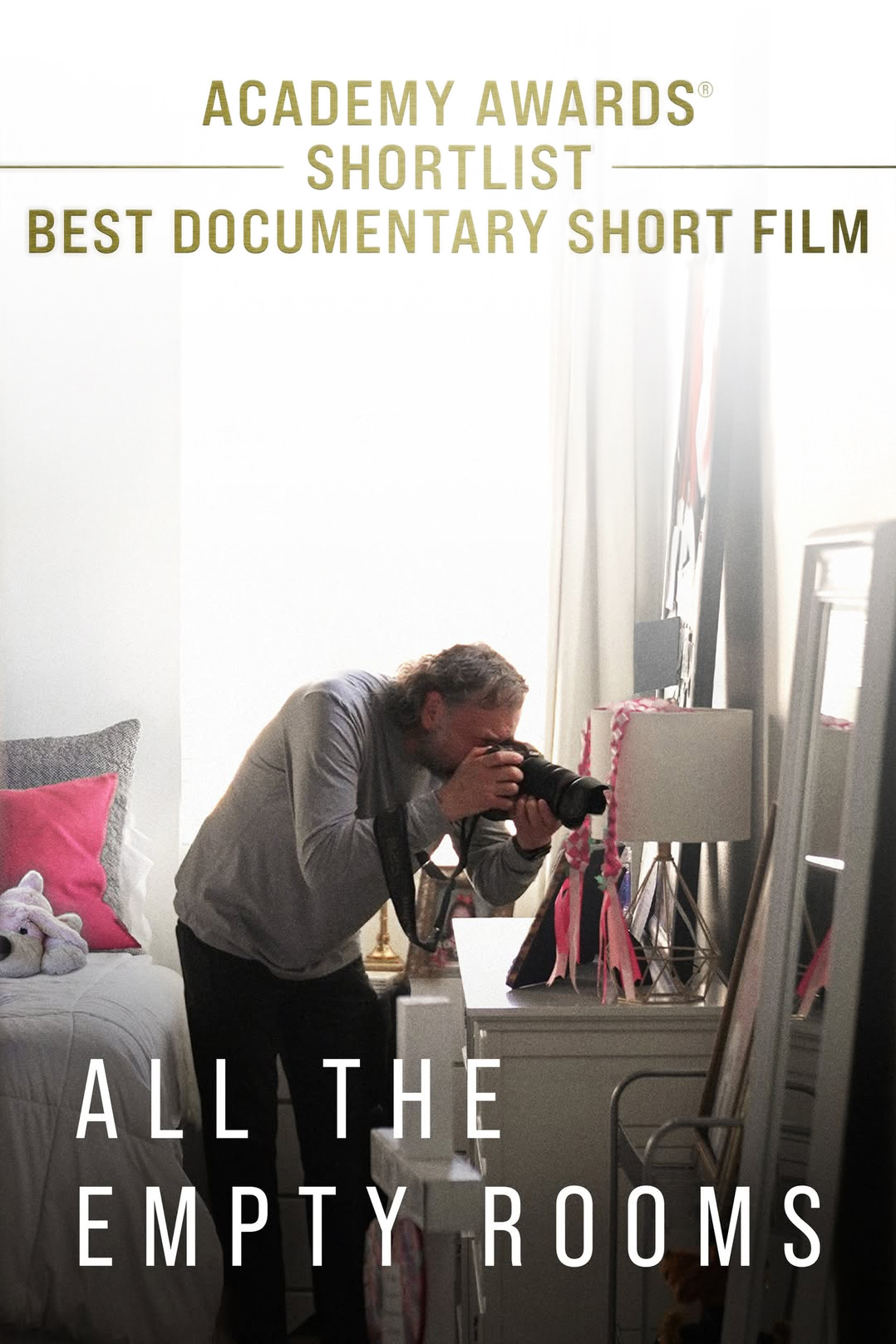

Meanwhile, Jones’ latest project, “All the Empty Rooms,” premiered at the 2025 Telluride Film Festival, where it was the first film sold. It began streaming on Netflix on December 1 and is currently shortlisted for the 2026 Academy Awards for Best Documentary Short Film. The multiyear undertaking follows news correspondent Steve Hartman and photographer Lou Bopp as they document the empty bedrooms of children who died in school shootings. Decider describes the film—released in a year in which the U.S. witnessed more than 75 school shootings—as "a difficult but powerful 35 minutes."

Both “Appalheads” and “All the Empty Rooms” draw on a sense of place, and explore notions of collective empathy. “Once the news cycle has finished and people are left with empty rooms, or in my town, the flood that is in my film, people are left with a shell of the home they had,” White observes. “The community members are still around them and still there. And there is a lot of love and support. And I think you do see people do the right thing and help lift each other up and just be there for each other.”

Here, White and Jones further reflect on the importance of community, connection, and how film can increase empathy and understanding.

Filmmakers Anna Richardson White (left) and Conall Jones. Photos by Kelsey Wisdom.

So, here you are, two accomplished filmmakers living in Carmel Valley. But you haven’t exactly known each other all that long. How did you meet?

ANNA: Our family moved down here during Covid. And then friends from Palo Alto had moved down as well, and I was talking about my film, and this friend was like, I met a guy who made a short documentary that was nominated for an Oscar. You should meet him. And I was like, yeah, I would love to. She actually didn’t even tell me how lovely Conall is. She was like, ‘He’s great.’ I didn’t have much context.

CONALL: Yeah, same for me. She said you were doing a documentary about your dad, but she didn’t give me a picture of all of you, as well, and what the film was. So, it was great to discover that, because at first I thought, ‘It’s a documentary about your dad… Okay, I need to know more. It can’t just be that.’

Anna, “Appalheads” is your first film, and so this is your first time on the film festival circuit. How is that experience?

ANNA: Well, let me just say, Conall is one of the people who gives me the most advice about doing the festivals. It’s hard, because it’s validation and rejection and validation. You get into one festival, you don’t get into others. I think I have gone in with the mindset that at least I’ve made a film that documents this thing my parents did and the legacy of Appalshop. And, at best, a lot more people get to see it if I find a distributor. I’ve won a couple of awards at festivals, but maybe it goes on to be something even bigger, which would be amazing. But I’ve been pleasantly surprised at any good thing that has happened. There is this narrative of ‘nothing good’s going to happen with your film.’ And I don’t know if I believe that.

CONALL: You have to refuse to believe that.

A film poster for "Appalheads," (left), and images from the short documentary. Photos courtesy of Kentcali.

One of the connecting threads between your two films is that they are trying to connect people by increasing collective understanding and empathy about other people’s experiences, about where you’re from, about loss.You’re both trying to achieve that goal, but in different ways.

CONALL: That definitely is a big part of it, with everyone being just so numb and desensitized, and everyone’s on their phones and actually feeling more disconnected. So then, how do you make a film that makes people feel more connected? You’re making a two-dimensional product to make people feel more connected, so it’s challenging. But this idea to document the rooms really resonated big time with myself and Josh [Seftel, the director of “All the Empty Rooms”].

What the news does is they’ll put up a portrait [of a school-shooting victim], and they’ll have a little anecdote about the kid. But that’s not working. You have to say, ‘hey, they had a room, they had a bathroom where they’d brush their teeth every day, and it’s still there.’ That finally resonates.

ANNA: It’s also the longer-standing of loss. The photo flashes on the screen during the news, and then it’s just gone. But if you think about this three-dimensional place where they lived, and then, what, as a parent, what do you do? I also think that during these moments, once the news cycle has finished and people are left with empty rooms, or in my town, the flood that is in my film, people are left with a shell of the home they had. The community members are still there. And there is a lot of love and support. And I think you do see people do the right thing and help lift each other up and just be there for each other.

CONALL: And that’s not ever shown.

ANNA: Very rarely. Every once in a while, someone will do a look-back six months on, or one year on, to see how these folks are doing. But I think one of the problems is that natural disasters are happening more often—and more often on a greater scale. And school shootings keep happening, so that there’s not a lot of time to go back and look.

Conall, when you were filming, was it apparent that victims’ families had felt supported by their communities and neighbors? Did they talk about that?

CONALL: Definitely. For example, there was Gracie–who’s at the end of the film. The night it happened, it was the most moving thing—Brian, the dad, can’t even talk about it without crying. They were in Gracie’s room, bawling, and they heard a commotion outside. All of their neighbors and friends had shown up with these candles in bags and they lined the street outside the house. So, when they looked outside, everyone they cared about was out there.

ANNA: Did you have trouble sleeping while making the film?

CONALL: No, not trouble sleeping. I mean, I worry about [school shootings]. I cried a lot. My emotions live a little bit closer. Or I’ll catch myself and be like, ‘Okay, I need a moment’ and step away. We had counselors talk to us before, during, and after production. So, that helped.

Scenes from "All the Empty Rooms," which premiered Dec. 1 on Netflix. Photos courtesy of Smartypants

Both your films deal a lot with a sense of place and connection to a place. That could be a community or it could be home. A room, specifically. Or, Anna, for you, going back home.

ANNA: The idea of home was really the premise of the film. How do we help people understand where I'm from so they think differently about it? And then maybe in turn I can understand where they're from. We really need that right now.

You each had very different paths to living in Carmel Valley. How would you say this area has shaped you?

CONALL: It's definitely shaped me. I do have concerns about isolation out here sometimes. That's why I think community and neighbors are important. There were a lot of kids my age where I lived growing up, in Cachagua, and there’s no one around. There’s no neighbors. To ride your bike into town, it took 45 minutes. [Town being Carmel Valley Village.] Are you going to do that? Sometimes I did. But you’re just isolated.

I tell people that move here that you have to contribute to Carmel Valley in some way. You have to be a coach, you have to pick up trash, or something, because it’s an unincorporated area. There’s no mayor, no public services. You have to pitch in some way. And it’s not even just the act. It’s just getting yourself out there, and then you feel more connected.

ANNA: I had a similar childhood. It was rural, there wasn’t a ton going on, so we had to create our own fun. And we had influences that weren’t very positive. So, all the stuff you saw, we probably saw, too. But now kids can just ask Google, and they can see all sorts of stuff.

But living here now, in Carmel Valley, I think I have more appreciation for the natural landscape. Where I’m from in Kentucky, it’s beautiful. But when I was growing up, there was a lot of active coal mining. You would hear dynamite, there was really no wildlife. Now, when I go back, the coal is gone, there are animals. There will be a baby deer nursing on the mommy in the middle of the road. There’s beavers. My mom and dad had a black bear on their back porch. But growing up, I didn’t really have that. And out here, the culture of hiking, and the culture of being on the beach, walking on the beach—I try every day to get out in nature for an hour and walk. I really appreciate that.

Anna, the way you describe where you grew up, that really speaks to the need of setting up Appalshop to bring something to the community, to contributing to it.

ANNA: It definitely has. And what’s cool is that the name of the film is “Appalheads,” which was really kind of a disparaging name. [“Appal” being short for “Appalacia”.] But now it’s said as a term of endearment, if it’s said at all. The younger generation, they really don’t use it like that, because they’re just like, ‘Oh, Appalshop is cool, it’s been here for 60 years.’ It’s just part of town. It’s like the hospital, Appalshop, the grade school. Which is just kinda cool.

CONALL: That’s a victory.

ANNA: Totally. And I don’t think my parents ever would’ve thought… In the film, I ask my dad if he felt like an outsider, and he says it was about the work. Which I just love, because I feel like it is about the work. It’s about the stuff you’re doing. And I think if more people had the opportunity to do the stuff that they really loved—and not what they felt like they had to do, or that society told ’em to do—I think our whole country would be in such a different spot. <img src="https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/6457f19f1c1e1601e2c9c3f6/6487a9355b63a6818c705cea_CC-Icon--20.svg"alt="CC"height="20" width="20">