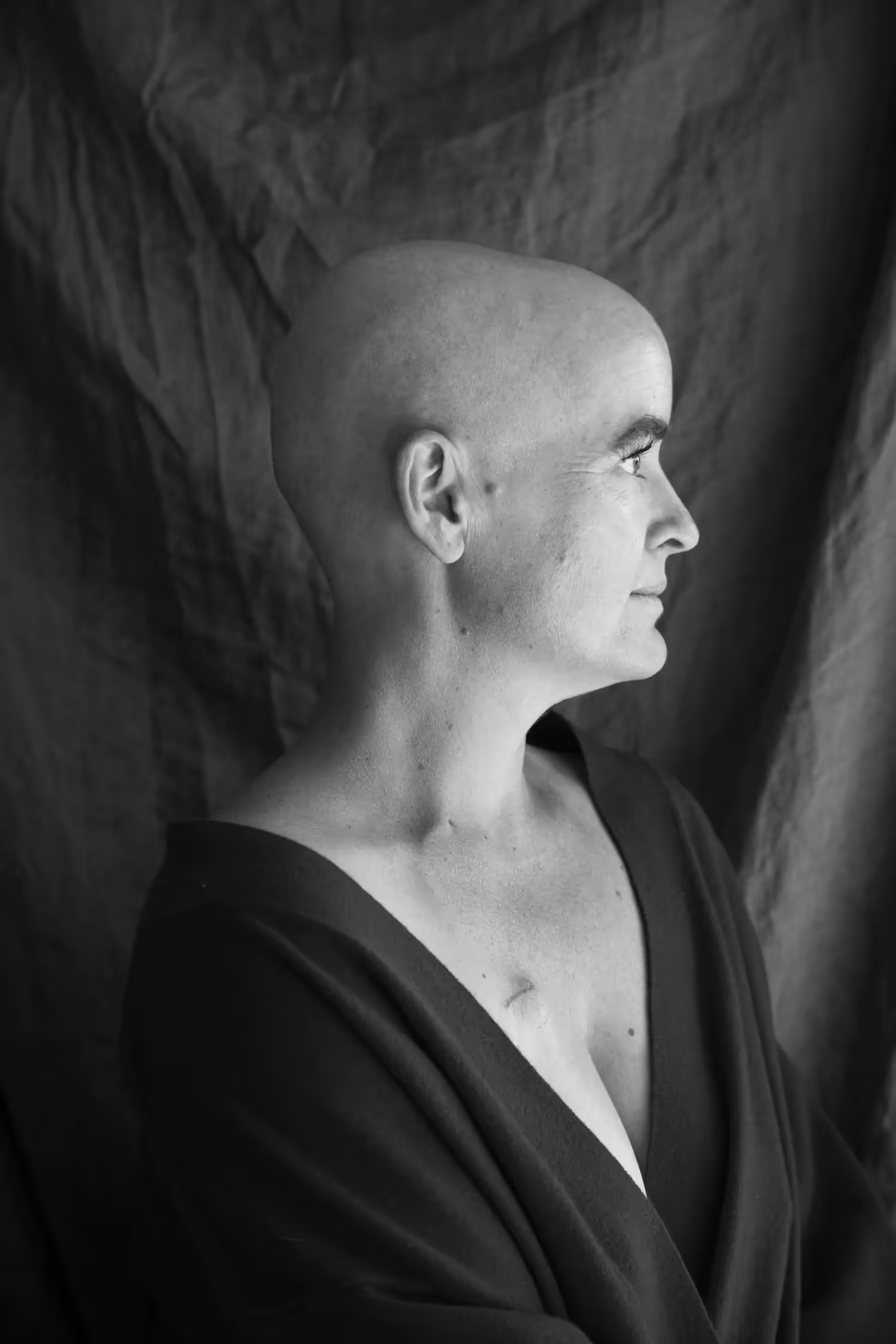

Grace Under Fire

Words by Jeanne Cooper

Photos by Kelsey Wisdom

Sarah Hawthorne does not believe in keeping secrets—at least when it comes to topics that were once taboo, and may still be distressing to some. For this beloved Carmel Valley preschool instructor, talking about the challenges she has faced teaches others they are not alone.

“Historically, you don’t talk about child loss, or suicide and being bipolar, or having cancer,” says Hawthorne, who at just 40 has experienced them all. “I have no shame surrounding it, or secrecy. I love sharing my story, because I feel whenever I share, if I can reach one person who can feel less alone in their own struggle, then it’s worth it to me.”

Hawthorne’s mental health issues began in her late teens, after growing up in Carmel Valley as one of three children of Robert and Cynthia Talbott, of Talbott Vineyards and Talbott Ties fame. While a student at St. Mary’s College in Moraga, she began struggling with feelings of depression. “It wasn’t situational. I felt a chemical imbalance in my brain,” she recalls. “There wasn’t anything in my life to propel me into this depression, which started years and years of being on and off medication that never really helped. I essentially had a misdiagnosis of general clinical depression.”

In 2012, about a decade later, Hawthorne says, she became “super depressed” again, despite being married to a husband she adored—metal artist Taylor Hawthorne, whose family founded Hawthorne Gallery in Big Sur—and having her “dream job” as a preschool instructor. In 2013 she attempted suicide and was hospitalized, leading to a corrected diagnosis of bipolar disorder. “That was amazing,” Hawthorne says. “When I hit rock bottom is when I got the help that I needed.”

“When I hit rock bottom is when I got the help that I needed.”

<div class="quote-attribute">Sarah Hawthorne</div>

She learned from her doctor that some people become more depressed, or even suicidal, when taking antidepressants—which is what she believes happened in her case. As she gained clarity around her own diagnosis, she realized that her story had the power to help others. “As soon as I started talking about my own mental health challenges, I realized there is more to be said about it, because there are so many people struggling and just feeling alone,” Hawthorne notes.

She and her husband celebrated the birth of their first children, twins Breyer and Angus, in mid-December the following year. Delivered at 32 weeks and four days into her pregnancy, the two boys had to stay in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) until finally coming home Dec. 23. “They were doing so well,” Hawthorne says.

But tragedy struck five days later, while she was nursing Breyer at a family barbecue. Although Breyer had been the stronger of the two twins, weighing nearly 5 pounds at 35 weeks, his heart inexplicably stopped beating.

“I had him on my shoulder and I was burping him, and when I brought him back down he wasn’t breathing,” Hawthorne recounts. “Being a teacher, just a few months before, I’d had a refresher course on CPR and had a session on infants, so I knew what to do and told my husband to call 911. I’ve always been really good under fire. When there’s a crisis, I just get really calm and still inside, and just know what to do.”

She continued to administer CPR while the paramedics prepared to take him to the hospital via ambulance. But the nearby Community Hospital of Monterey Peninsula wasn’t able to treat infants as young as Breyer, who had been without oxygen for 45 minutes, according to Hawthorne. Instead, Breyer’s dad accompanied him in a medical transport to the NICU at UCSF.

“Before he was taken by helicopter, I went into the ER and I said, “Hi Breyer, Mommy’s here, and I put my hand on him and his heart started for a second,” she recalls. “He got a heartbeat. The nurses all said, ‘Oh, Mom’s here.’ He knew I was here and they’ve seen it before…I now know he was saying goodbye.”

“Before he was taken by helicopter, I went into the ER and I said, “Hi Breyer, Mommy’s here ... his heart started for a second.”

<div class="quote-attribute">Sarah Hawthorne</div>

The next night, Hawthorne says she and Taylor were given “a choiceless choice” of leaving Breyer on life support or taking him off. He had no brain activity, so they decided on the latter course. Hawthorne says she has come to terms with his brief time on earth. She cherishes the memories of her “calm, clear-eyed baby,” an “old soul” who looked everyone right in the eyes from birth.

“We’ve had moments of ‘Why us, why did we have to lose him?’ But for the most part, there’s this overwhelming sense of he wasn’t supposed to stay with us,” Hawthorne shares. “We wanted him to stay with us, but it just wasn’t his story. … He had been here before so many times and just had something else to do. He brought his brother to us and he had other work to do.”

Hawthorne would have more work to do, too.

It was Summer 2021. Angus was now 6 years old, and his little brother, “rainbow baby” Crosby, was 4. For Hawthorne and her young family, life was going reasonably well, when she detected a small lump in her left breast. As anyone in Hawthorne’s situation would fear, it proved to be cancerous. Triple-negative breast cancer, to be exact, a particularly fast-spreading form of the disease that required a quick and aggressive response.

Long obsessed with threes, Hawthorne says the diagnosis seemed like the “closing of a triangle” after her suicide attempt and loss of a child. “I felt almost a sense of gratitude for what I had been through, because (it) prepared me for this new challenge that had been thrown before me,” she says.

With the help of her oncologist, Dr. Nancy Tray, who called Hawthorne a “fighter,” she threw herself into this new battle while keeping her calm perspective. “My whole life I’ve had the ability to just accept things right away and move forward. This is the way it is, it’s one part of my narrative. I’m in control, not the cancer,” Hawthorne explains.

“A lot of people let it take over them, and I understand why. But like losing a baby, I won’t let it define me. When we lost Breyer, my husband Taylor and I both knew it wouldn’t define who I was as a mother or who our family was. Same with cancer—it’s not who I am, it won’t eclipse my personality,” she adds.

"(Cancer) is not who I am, it won’t eclipse my personality.”

<div class="quote-attribute">Sarah Hawthorne</div>

As a mother of two young sons, Hawthorne also had to accept the help of family and friends. “I really had to rely on my support team. It felt like when we lost Breyer, we had to rely on people around us and realize the community is so important. We had people picking our kids up from school and arranging playdates, we had this meal train that went on forever,” she says. “We had friends texting and checking in and just felt so supported.”

It's now been more than a year since her last immunology treatment, and she’s happily back to teaching 2- to 6-year-olds. She also has more to share with adults.

“I do believe everything happens for a reason and that there aren’t really any accidents,” Hawthorne says. “I don’t know where this is all supposed to lead, but I realize that a lot of my contemporaries haven’t been through these things. I’m compelled to believe that sharing my story is part of it. If it helps even one person feel less alone, it’s worth putting myself on the line and saying, ‘This is how I got through it.’”

If you or someone you know is struggling with thoughts of suicide, free and confidential help is available 24/7. Call or text the national Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988. <img src="https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/6457f19f1c1e1601e2c9c3f6/6487a9355b63a6818c705cea_CC-Icon--20.svg"alt="CC" style="display: inline-block; max-width: 100%; min-width: 12px; width: 12px; height: 12px;">

____

Jeanne Cooper worked as a news and features editor and writer for the Washington Post, Boston Globe and San Francisco Chronicle before going freelance in 2008. Her family ties to the Monterey Peninsula date to the early 1950s, when her grandfather helped establish the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey.